Computed properties are part of a family of property types in Swift. Stored properties are the most common, saving and returning a stored value, whereas computed ones are a bit different.

A computed property, it’s all in the name, computes its property upon request. It can be a valuable addition to any type to add a new property value based on other conditions. This post explains how and when to use them, as well as the differences between a computed value and a method.

What is a Computed Property in Swift?

A Computed Property provides a getter and an optional setter to indirectly access other properties and values. It can be used in several ways.

An everyday use case is to derive value from other properties. In the following example, we’re creating a filename based on the name and file extension:

struct Content {

var name: String

let fileExtension: String

// A computed property to generate a filename.

var filename: String {

return name + "." + fileExtension

}

}

let content = Content(name: "swiftlee-banner", fileExtension: "png")

print(content.filename) // Prints: "swiftlee-banner.png"As you can see, the filename property is computed by combining both the name and fileExtension properties. Note that we could simplify this code by removing the return keyword:

// A computed property to generate a filename.

var filename: String {

name + "." + fileExtension

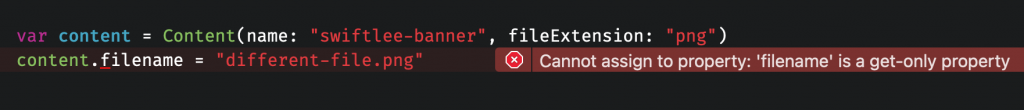

}The filename property is read-only, which means that the following code would not work:

You could make this more explicit by adding the get wrapper around your computation:

// A computed property to generate a filename.

var filename: String {

get {

name + "." + fileExtension

}

}However, it’s best practice to simplify the code and remove it as it’s not adding much value if you know what computed properties are (which you do after this post! 😉 )

Using a Swift Computed Property to disclose rich data

Until now, we’ve only covered read-only Computed Properties, while it is also possible to add a setter. A setter can be helpful when you want to prevent access to a more enriched object in your instance.

For example, we could keep our model object private inside a view model while we make a specific property accessible with both its getter and setter:

struct ContentViewModel {

private var content: Content

init(_ content: Content) {

self.content = content

}

var name: String {

get {

content.name

}

set {

content.name = newValue

}

}

}

var content = Content(name: "swiftlee-banner", fileExtension: "png")

var viewModel = ContentViewModel(content)

viewModel.name = "SwiftLee Post"

print(viewModel.name) // Prints: "SwiftLee Post"Our Computed Property name serves as our public access point to the inner content value, without revealing too much about our backing model to implementors.

Computed Properties inside an extension

A great thing about Computed Properties is that you can use them inside extensions, too. We could, for example, create quick access to the width and height of a rect:

extension CGRect {

var width: CGFloat {

size.width

}

var height: CGFloat {

size.width

}

}

let rect = CGRect(x: 0, y: 0, width: 320, height: 480)

print(rect.width) // Prints: "320"Overriding Computed Properties

Within subclasses, you can override read-only properties using Computed Properties. This can be useful in custom classes as well as when working with UIKit instances like UIViewController:

final class HomeViewController: UIViewController {

override var prefersStatusBarHidden: Bool {

return true

}

}We could even make a such property configurable by a backed stored value:

final class HomeViewController: UIViewController {

private var shouldHideStatusBar: Bool = true {

didSet {

setNeedsStatusBarAppearanceUpdate()

}

}

override var prefersStatusBarHidden: Bool {

return shouldHideStatusBar

}

}Throwing an error from a Swift Computed Property

It’s possible to throw an error in case a computation fails to match a requirement. For example, we could update our filename property and throw an error in case the file extension was found empty:

struct Content {

enum ContentError: Error {

case emptyFileExtension

}

let name: String

let fileExtension: String

/// A computed property to generate a filename.

/// Throws an error when the file extension is empty.

var filename: String {

get throws(ContentError) {

guard !fileExtension.isEmpty else {

throw .emptyFileExtension

}

return name + "." + fileExtension

}

}

}

/// We now need to use the `try` keyword when accessing:

print(try content.filename) // Prints: "swiftlee-banner.png"Using an async getter

Finally, it’s also possible to define an async get to allow using await inside the getter. For example, we might introduce a backend to validate the filename before returning:

struct Content {

enum ContentError: Error {

case emptyFileExtension

case invalidFilename

}

var name: String

let fileExtension: String

// A computed property to generate a filename.

var filename: String {

get async throws(ContentError) {

guard !fileExtension.isEmpty else {

throw .emptyFileExtension

}

let filename = name + "." + fileExtension

let isValidFilename = await backend.validate(filename)

guard isValidFilename else {

throw .invalidFilename

}

return filename

}

}

}

/// We now need to use the `try` and `await` keyword when accessing:

print(try await content.filename) // Prints: "swiftlee-banner.png"This is part of Swift Concurrency, for which you can learn more by following my dedicated course: www.swiftconcurrencycourse.com.

FREE 5-Day Email Course: The Swift Concurrency Playbook

A FREE 5-day email course revealing the 5 biggest mistakes iOS developers make with with async/await that lead to App Store rejections And migration projects taking months instead of days (even if you've been writing Swift for years)

When should I use a Swift Computed Property?

It’s important to understand when you should use a Swift computed property over a stored property. Use it when:

- It depends on other properties

- You’re defining the property inside an extension

- The property is an access point to another object without disclosing it fully

Although this should help you to decide when to use them, it’s still often a case-by-case decision. My personal preference is to start with a stored value whenever possible. This mostly depends on the above conditions, as well as on whether the property depends on the state. If your computed property derives its value from two static properties, it might be better to create a static property for your derivation, too, to prevent unneeded calculations.

Taking into account performance when defining properties

To explain the previous paragraph in a bit more detail, I’d like to shine a light on performance. A Swift computed property performs its operations every time it’s called. This means that a heavy operation can easily result in a performance decrease.

Let’s explain this using the following code example:

struct PeopleViewModel {

let people: [Person]

var oldest: Person? {

people.sorted { (lhs, rhs) -> Bool in

lhs.age > rhs.age

}.first

}

}

let peopleViewModel = PeopleViewModel(people: [

Person(name: "Antoine", age: 30),

Person(name: "Jan", age: 69),

Person(name: "Lady", age: 3),

Person(name: "Jaap", age: 3)

])

print(peopleViewModel.oldest!.name) // Prints: "Jan"As you can see, we have a view model for people that contains a collection of Person objects. We have a computed value to get the oldest person in the list.

Every time we access the oldest person, we’re going to sort the collection and return the first element. In this case, we know that we have a static list of people, so we can rewrite this logic and calculate the oldest person once upon initialization:

struct PeopleViewModel {

let people: [Person]

let oldest: Person?

init(people: [Person]) {

self.people = people

oldest = people.sorted { (lhs, rhs) -> Bool in

lhs.age > rhs.age

}.first

}

}This way, we know for sure we’re only doing the calculation once, and we could easily gain some performance wins.

Obviously, this is a case-by-case scenario, but it’s essential to consider this when defining your properties. Computation happens on every access, so switch to a stored alternative if these are heavy calculations.

Computed Properties vs Methods in Swift: When to use which?

Another common question is when to decide to use a method instead of a Swift computed property. There’s no common sense in this regard, but there are a few obvious reasons.

Properties, for example, won’t take any arguments. If you want to mock a value for tests or if you want to change one of the input parameters dynamically, you’re likely going to need a method.

I like to take readability and understanding of my code into account when making this decision. I prefer to use methods when the logic I’m about to write involves heavy calculations that may take longer to execute. It’s a way to let implementors be conscious about using logic and prevent performance drains. Properties are tempting to use and are often seen as lightweight values, which makes it a risk if they contain heavy operations.

Conclusion

Computed Properties are part of the basics in Swift. They can be used in many different ways, and it’s essential to know the various use cases. Always take performance into account and try to prevent unneeded calculations if possible.

If you like to learn more tips on Swift, check out the Swift category page. Feel free to contact me or tweet me on Twitter if you have any additional tips or feedback.

Thanks!